For What It’s Worth

I’m wanting to jump past this part

of my book. It’s not very political? It’s irrelevant, supposedly political and

yet decidedly apolitical?

My Own Identity

Politics? Within this highly charged—downright electric—landscape in which

nations were literally emerging, a writer-like person was hiding out too: and

yet, I’d persist haplessly in a foreign terrain. I was a lost cause, a writer already

undercover, pretending in politics.

It’s my summer in

the Soviet Union. Yes, that Soviet

Union.

My part of the Soviet

Union was as you might imagine it to be: colorless high rises and patches of

weeds stretching throughout haunting projects, a grayish pallor over a city

crisscrossed with tram wires overhead and situated on top of a metro system

that reeked of infinity and unhappiness and industry and dank urbanity, trousers

with holes on sad men, ripped stockings not worthy of being called nylons on

women with unfashionable purses, Orwellian grocery stores with nothing on the

shelves, crazy old ladies yelling random Russian shit at our brazen American

streetwalking, so many serious faces—on children even. Leningrad (now St.

Petersburg) was a cosmopolitan disaster: punctuated by beautiful churches with

onion-bulb tops, gold-plaited estates once occupied by Czars, and the Hermitage

with its trove of world art hung in slapdash splendor across palatial walls

papered in thick red velvet—the very site at which the 1917 Bolshevik

Revolution happened and the royal family was led to a bloody slaughter except

for, maybe, Anastasia.

I don’t really

know where Putin was just yet. Doing KGB stuff, perhaps. I actually think we

were both at the same university at the same time, but—right then, in 1990—Gorbachev

was in power, and he was a good guy! Glasnost

and perestroika were the buzzwords: openness and reconstruction. It was almost all over for the U.S.S.R.; the Iron

Curtain was coming down. Boris Yeltsin was making waves, and people were

talking. The Eastern European Bloc had fallen apart, mostly in 1989. The Berlin

Wall was in shards. Plus, Iraq was on the verge of attacking Kuwait.

And I was just a

college girl studying political science.

And

Russian.

Because

I wanted to be a diplomat/U2 ambassador/world-traveler.

Because

of Cold War thinking.

Because

of a boy who also took Russian.

So,

yeah, I think I ended up taking three years of the language, two years of

Russian Humanities, and a Soviet Politics class.

Do not speak to me in Russian.

Do. Not. Do. It.

Madonna

posters adorned Helsinki, where we landed and walked around for a few hours in

the bedazzling glories of European capitalism, replete with chiseled cheekbones

and Nordic good cheer. We took a train into Leningrad—a scary sleeper train

straight out of Anna Karenina (and

you know how that ended) which rattled along old tracks leading from Finish Grandeur

into Dictatorial Hell. We were, the group of college kids and the professors

from Arizona, fearful of Commies and of anal probes because we didn’t have the

right papers.

In

the summer of 1990, I went on a Russian Language program to Leningrad for four

weeks (with a fifth week in Moscow). After the academic program, I met friends

and we spent the rest of the summer in Europe.

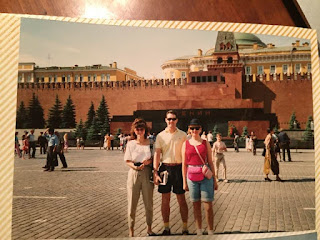

I look at the

snapshots.

They’re all that’s

left.

I’ve lost my

language skills completely.

Man and Woman on Red Square, Moscow (July 1990)

Walter is in his

early thirties, so he’s old. I’m twenty, and though I wish I could say my hair

is brassy or sun-drenched, it’s bozo-red.

I’m in travel mode: wearing glasses, a tie-dye top, a vicious pink fanny pack.

Walter

is Canadian and possibly a business management professor at Harvard. I’m not

sure. He’s dapper-ish, maintaining a level of attractiveness that eluded me.

I’m not into him, because my affections are elsewhere, but we do tend to move

in the same Russian Language Emersion Program circles.

Actually,

he’s had a fling with one of the pretty girls on our program, even though he’s

in a relationship at home in Canada or Harvard.

I

say to him one time when we’re alone, “But you have a girlfriend?”

Walter

gives me some line, like, What happens in

the Soviet Union stays in the Soviet Union.

Oh.

But

we are in Moscow now, and the trip is almost over. He will return to Canada or

Harvard, and I will move on to Europe. Walter says to a group of us standing on

Red Square, “I’m not going to pretend we’re keeping in touch, because we

won’t.” He looks at all of us, students before the Kremlin. “So don’t write.”

The fling girl is

older than I, cute, worldly, not torn apart or anything by his indifference.

On Nevsky

Prospect, back in Leningrad, she had shared an ice cream cone that was dripping

from both ends with this other American kid on the program. Walter and I had

watched. A seductive, titillating sight. He had not cared, either.

The

Twenty-Eighth Communist Party Congress is about to begin. Dan Rather is

somewhere around. Lenin’s Tomb is still there.

During the past

month, I’ve eaten a hairball baked into my breakfast, attended the world-famous

Bolshoi Ballet sans Barishnikov who’s probably home in Manhattan, and eaten at

the brand new McDonald’s in Moscow. I’ve attended the circus with my

professor—it was utterly devoid of weirdness (why the hell not?). I’ve gone to

Peter the Great’s glamour-pad palace on the outskirts of Leningrad, and I’ve

shadowed Dostoyevsky on imagined Russian paths. Pushkin, Gogol, and Checkov

whisper constantly in our ears—and though I am officially in Soviet territory

on political business, I am secretly a writer taking notes. I’m just watching

people, a voyeur, a literary pornographer.

In

the middle of Red Square, Walter—Wall

Street Journal tucked under his arm—looks in my direction and says to me,

an unglamorous girl with a hot pink fanny pack around her waist, “Out of all

the people on this trip, you’re the one I’d like to know what happens to.”

You’re the one I’d like to know what

happens to.

Grammatically

awkward, utterly unprecedented.

His

comment is devoid of sexual intrigue, ulterior motive, monetary possibility.

It

is like the storming of my own Winter Palace.

And

so I went to Europe, and I never saw Walter again.

Since

then, there have been college degrees in unrelated fields. I’ve abandoned

careers and towns. Intellectual snobbery is my mink stole I’ve worn to parties

that I truly dread. Irresponsible debt gave me a good education. I waited for

heartbreaks to kill me, and they didn’t. My passport is stunning—stamped and

suggestive. Drag shows in Harlem, dinners at the Waldorf-Astoria, nights on

dung floors in Africa, holding babies in Shanghai orphanages, walks through

Roman ruins, hiding Cuban art in my suitcase when flying out of Havana. I

worked in Disneyland. I worked at Amnesty International, where I stole Harrison

Ford’s address from the P.R. person’s rolodex. I followed an elephant through

the Swazi bush.

There’s been a

coma and rehab and the death of a parent. For a full year, I did nothing. There

are people in my life who have disappeared completely. I wrote a poem once that

mentioned Dan Rather. It was very bad.

Walter, I’m this

other woman now.

I’ve published two

books, had two kids, lost two breasts, and suffered from insomnia.

I’ve married and

been separated. I once visited the apartment my husband was staying in while we

were apart and I moved through his rooms, looked in his fridge, wondered at his

life, saw it as a foreign country, contemplated renewing that visa.

I’ve stayed

state-side.

My

hair is still brassy, sun-drenched, bozo-red. But underneath the stain, it’s

fully gray.

Walter, where are you now?

Walter, what has become of you?

Have you headed into middle-age

with thinning hair and wrinkled skin?

Walter,

you are the Prufrock of my Soviet Summer.

Remember

when we spoke of Michelangelo?

If

you saw me now, if we were to meet at the Kremlin or at St. Basil’s, if we

happened upon each other on a flight out of Scandinavia: would you recognize me

today? Would you know who I am? Could you see past the skin damage, my flesh

now in ruins?

All

of our maps have changed, Walter.

Our

globe has shifted in unrecognizable ways, Walter.

Where are you now, Walter?

I

like to picture us in Antwerp or Brugge. We’d sit in a dark bar and show each

other pictures of our kids.

Walter, I’d say. Talk to me. Tell me

things.

My lost Walter.

If

we met today, in Portugal or Beijing, in New Delhi or San Salvador, would I

have to do all of the talking?

When

you’d throw your eyes over me as if I were naked and needed covering, when you

saw how time had elapsed on my face, when you tried to ignore the visible scars

on my body that hinted at a disaster far more serious than a hot pink fanny

pack—when you saw these things—after so many years, would you be disappointed?

Would

I disappoint you?

My Long-Gone Walter.

Are

you disappointed?

Comments

Post a Comment